Fruit fly behavior

A fly’s brain is vastly simpler than a human’s, allowing scientists to think about the nervous system in a comprehensive way. How do different parts of the nervous system coordinate to give rise to behavior? Luckily, despite their relative simplicity, fruit flies perform a ton of interesting behaviors! Do any of the following examples of ongoing Drosophila research inspire your own scientific questions?

Flies sleep (and wake up)

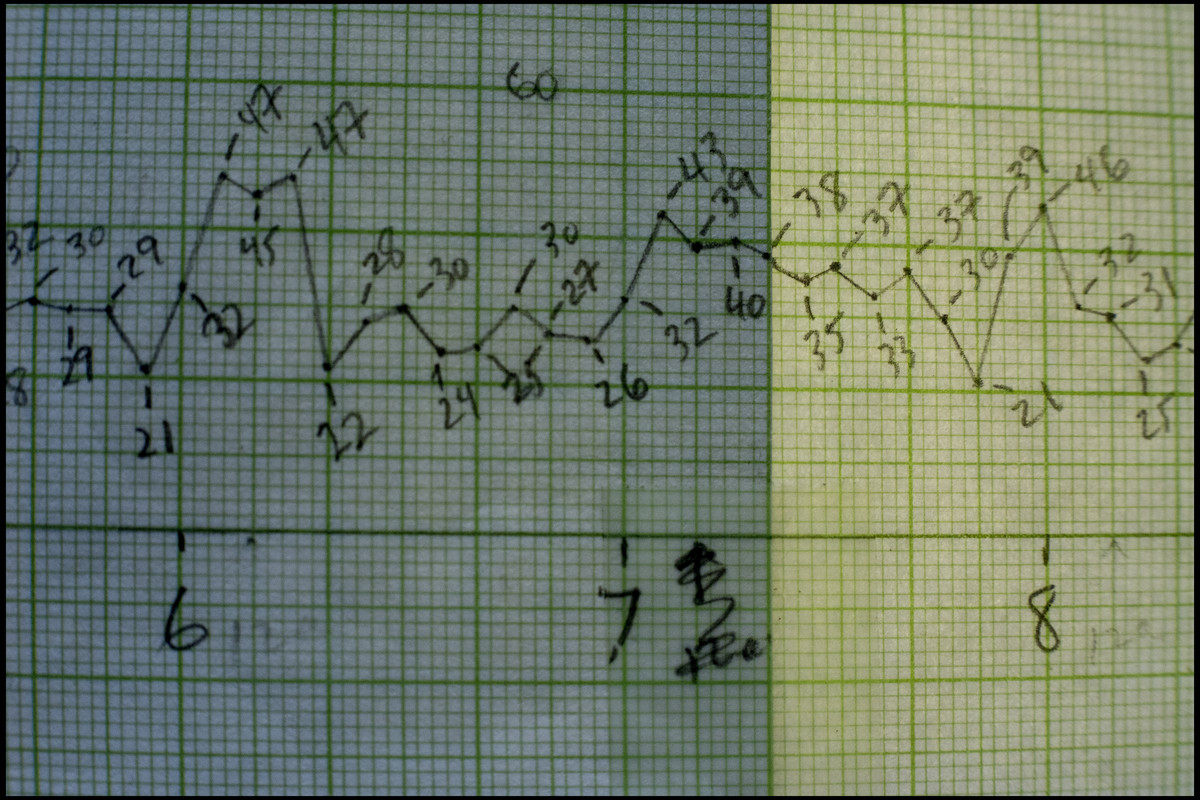

Fly sleep data recorded in the laboratory of Michael W. Young. Photo credit: Mario Morgado

Fruit flies behave according to circadian rhythms just as we do. They are highly active at dawn and dusk, but they sleep at night and take a long siesta in the middle of the day. Researchers know this, because they can put hundreds of flies in separate small tubes placed in an array so that a laser beam falls on the middle of each tube. They monitor the fly’s activity by counting how many times in a given period it breaks the beam, essentially giving them an idea of how much it is moving about inside its tube. Flies have two distinct periods of activity in the course of 24 hours, and years of research has shown that this rhythm of activity is set by a collection of proteins, collectively known as a molecular “clock”. There are many ways to disrupt a fly’s “clock”, often with significant consequences for other parts of the fly’s biology (something humans can appreciate, as well!).

What would happen to a fly’s natural sleep/wake cycle if you expanded or contracted the time between “dawn” and “dusk” each day? Are fly circadian rhythms particularly responsive to specific wavelengths of light? Perhaps you can test questions like this in your own experiments.

Read more about Drosophila sleep research at Rockefeller:

Discovery of “Clock” Proteins Governing Circadian Rhythm

The Genetic Basis of Insomnia in Flies

Social Isolation and its Effects on Sleep in Flies

They navigate

Deep in the fly’s brain is a set of neurons that act as a “compass”. They are constantly active as a fly moves through the world, and the specific pattern of activity serves as a readout of the animal’s heading relative to fixed landmarks in its environment.

Read more about research on Drosophila navigation at Rockefeller:

Discovery of a Fly’s Internal “Compass”

They learn associations

Much as your dog might learn to associate the sight of a leash with a walk, flies can learn to associate specific cues with a reward (like a sugar drop) or a punishment (like a mild electric shock). Ongoing research is elucidating the neurons and even the molecules that encode these associative memories. Can you design an experiment to test a flie’s learning abilities?

Read more about Drosophila learning research at Rockefeller:

How Flies Learn to Associate Smells With Experiences

They make complex decisions

Female flies prefer to lay their eggs in sugar-rich substances, because sugar will provide a good food source for the newly hatched larvae. Researchers have shown that female flies choose where to lay eggs based on the relative (rather than the absolute) “value” they place on specific sites in their immediate environment. So whereas an egg laying female will choose a slightly sugary substrate over a site with no sugar, she’ll avoid that same slightly sugary site if a very sugary site is also available to her. This shows that flies place relative value on different options to make complex decisions. When was the last time you did the same thing?

Read more about research on Drosophila decision making at Rockefeller:

How Flies Use Odor to Navigate

The Many Roles of the Dopamine

They engage in social behaviors

Flies tend to group together on food sources. A rotting banana can quickly become an almost chaotically social place. Study a group of flies closely to see if you can identify different social behaviors – courtship dances and small scale fights are very common!

Read more about research on Drosophila social behavior at Rockefeller:

How Male Flies Choose Their Mate

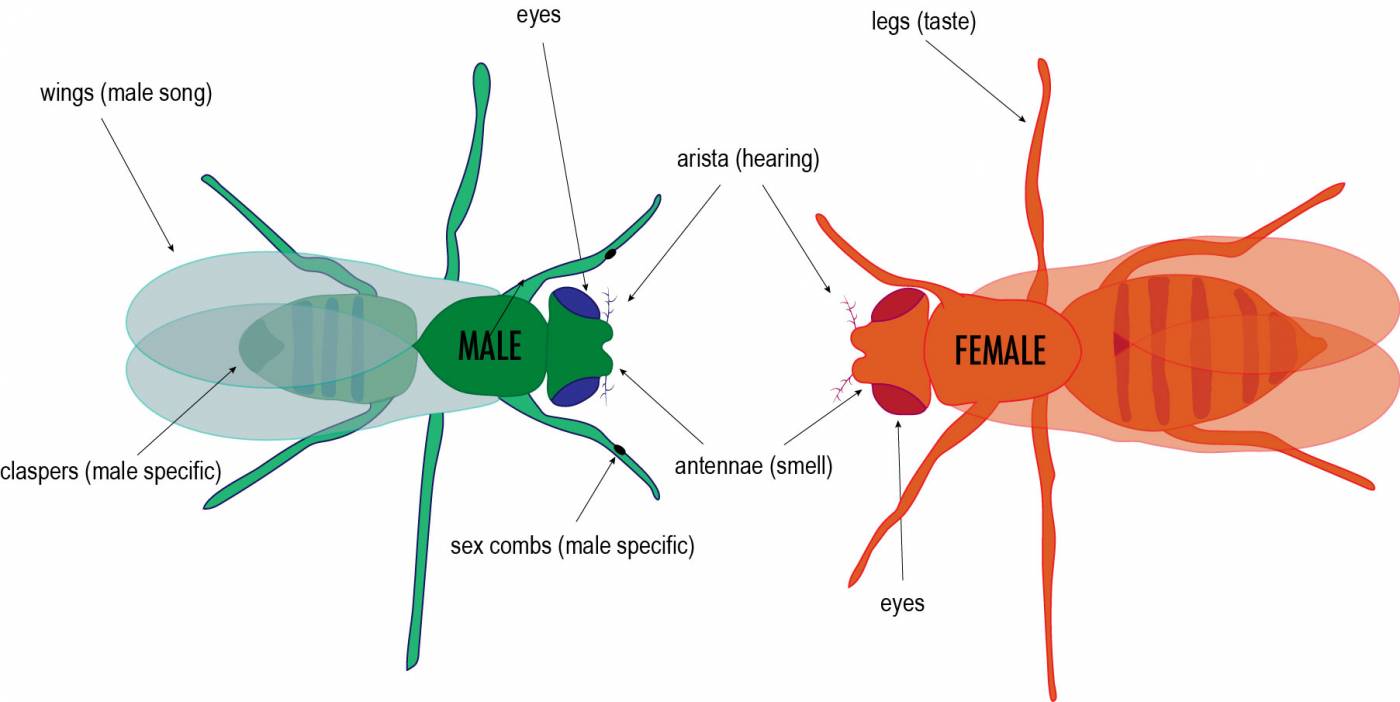

They sense the environment

Like us, flies can see, smell, taste, and sense touch. They also respond to temperature, water, and gravity. Smell is particularly important for flies. They use odor plumes from decaying fruit to efficiently navigate toward a food source. You may be well aware of this if you’ve ever had a fruit fly infestation near your fruit bowl! Try placing a container of apple cider vinegar outside (flies love this smell) to see if you can trap any wild fruit flies.

Observing flies as they engage in natural behaviors can inspire fascinating future experiments. In this way, a simple bottle of flies is an exciting starting place for a variety of science projects. As you can see, there’s a long history to studying flies and a variety of methods that scientists can choose to answer their questions. Research is only growing and evolving in new directions. What direction will you choose to take your own Drosophila research?