Covid in Context

We Have Been Here Before

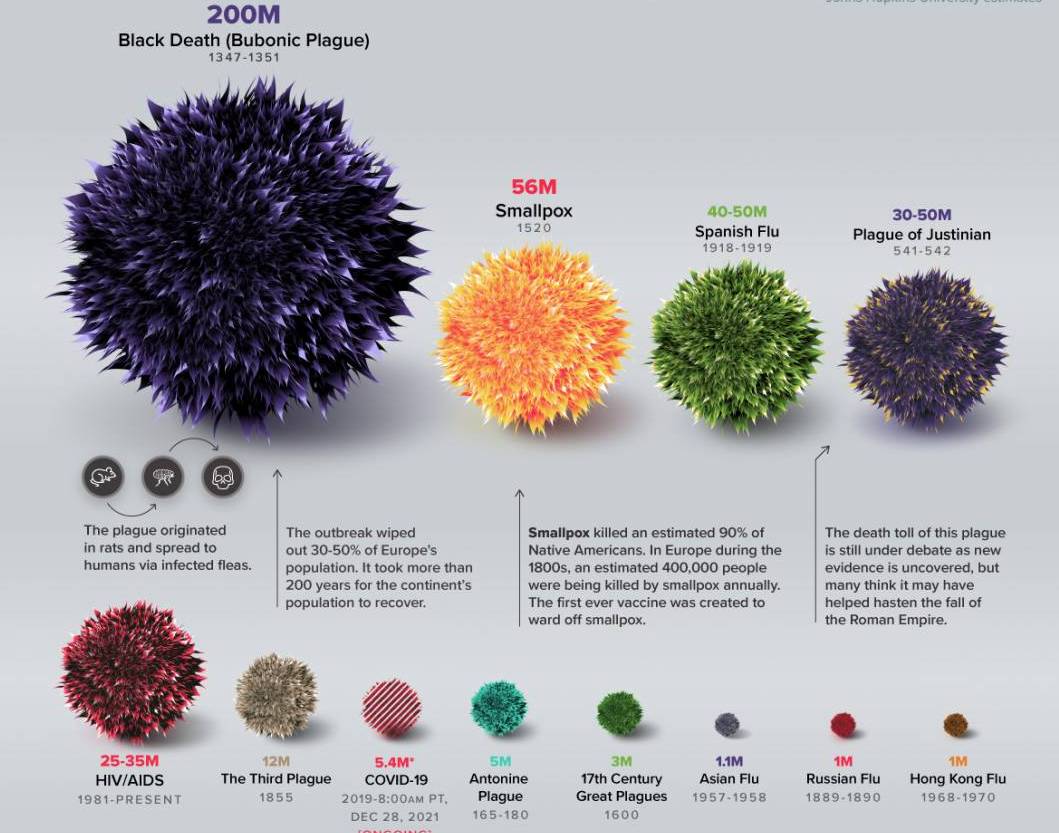

Humans are no strangers to massive viral disease outbreaks. When looking at the biological big picture, we humans are just another life form, living among many, many other life forms, big and small. All in all, we are simply symbionts in a dynamically evolving biological ecosystem — full of viruses. In fact, viruses are thought to be one of the most abundant biological entities on our planet. It’s no wonder that, over the course of human history, we have faced innumerable viral disease outbreaks, some of which took place at or near global scales.

Examples of historical viral pandemics, scaled to represented how many people perished as a result [Source: Visual Capitalist].

For as long as there have been viral outbreaks in human populations, there have been people who’s job it is to study these viral outbreaks. This certainly extends to the coronavirus species. Since the original SARS-CoV outbreak in 2002, coronaviruses have been carefully watched by the scientific community. In fact, in 2007, many coronavirus experts predicted that we would see another coronavirus outbreak in humans:

“The findings that horseshoe bats are the natural reservoir for SARS-CoV-like virus and that civets are the amplification host highlight the importance of wildlife and biosecurity in farms and wet markets, which can serve as the source and amplification centers for emerging infections” [read the article here].

This conclusion is from a 2007 meta-analysis of over 4,000 publications associated with the epidemiological, clinical, pathological, immunological, virological, and other basic scientific aspects of the SARS-CoV virus and the disease it causes. The world was not necessarily listening at the time. I mean, what are the chances that the virus they detected in horseshoe bats would jump into humans? [what a silly question in hindsight!]

To be quite honest, finding the perfect “conditions” to nurture a viral pandemic are not that easy. While there are millions of different virus types out there, each can only infect a specific range of cell types. Even more rare is when a virus gains the ability to jump from one host species to another — a concept known as zoonosis. In order for zoonosis to take place, two conditions must be met:

- A virus needs to have access to a new host

- The new host needs to have cellular receptors that match virus receptors in order for the virus to be taken up by host cells

With increasing modern lifestyles, an expanding human population, and unchecked climate change, the chances for humans to meet the above criteria get better and better. When it comes to viral outbreaks, humans are no strangers. But given the pressures to maintain modern life, it should not be silly to question not if we will be here again, but when.

COVID-19: A Pandemic for Modern Times

What do you remember about the onset of the pandemic?

In late January, 2020, I was wrapping up a work trip when I got a call from my husband, “I didn’t want to bother you but I have had a pretty bad fever for nearly a day and a half, and now Rubi [our then 10 year-old] is starting to burn up.”

I had been keeping an eye on the new coronavirus-like virus that was spreading across China earlier that month, and had recently read the news of a confirmed coronavirus case in the state of Washington. But I live in NYC, and probably like other Americans, felt a false sense of security. Everything seemed so far away! Even so, the news from home instilled enough worry that I packed my bags and re-scheduled my travels for earliest possible flight back home. It would be my last flight without a mask.

Over the next few weeks, the reality of a global pandemic began to sink in. Death tolls in China were surpassing what they had seen with the 2003 SARS outbreak. The CDC warned of an imminent pandemic, then the WHO officially made the call. On March 13, 2020, the United States joined many other countries in shutting down completely. Schools, stores, museums, restaurant dining: all seemingly gone. For most of us, at least those of us not on the front lines, it left us a lot of time to sit and stare at the influx of pandemic-related information being delivered through the fire hoses of the internet.

It started with asking: Where was the primary information on COVID19 coming from, and how was it being delivered to the masses? How were people interpreting and sharing information? And then it morphed into: How are people distinguishing pseudoscience and hyperbole from actual data, with appreciation for the limitations of our knowledge? Needless to say, it got messy, and in many cases, emotions reigned supreme.

Humans Slowed Down; Science Sped Up

Never before have we, as a global society, experienced — and benefited from — such a magnificent pace for scientific research. In less than a year, scientists went from the identification of a brand new species of coronavirus that can infect humans to the design and creation of an effective set of protective vaccines. To achieve this, and the many other incredible scientific benchmarks that have shaped our ability to combat the potentially deadly effects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, required significant scientific coordination, data sharing, and, of course, funding.

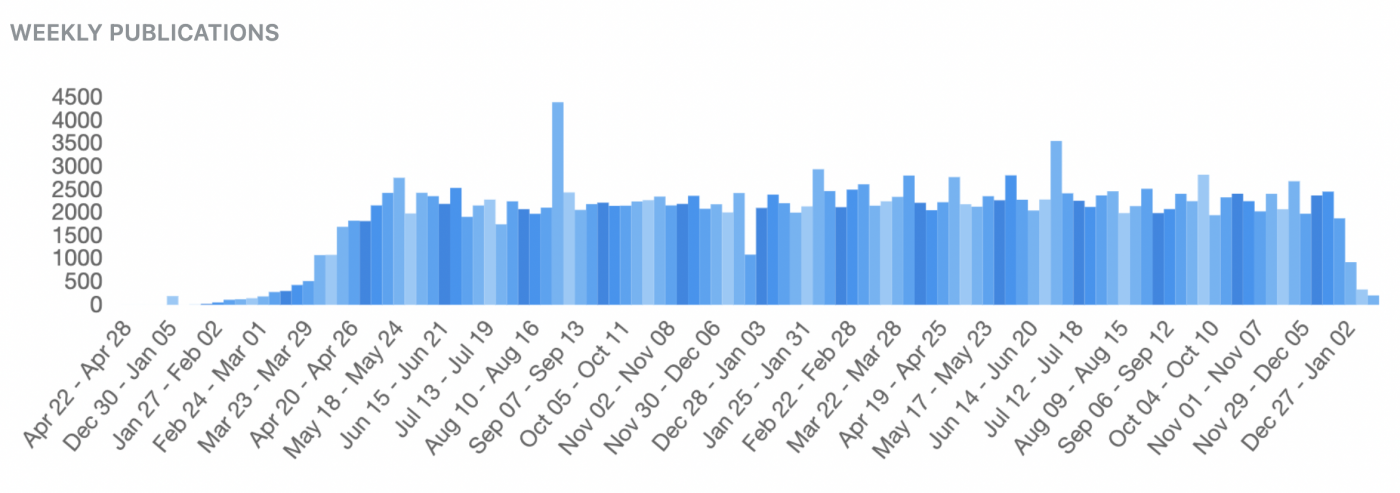

As laboratory power all over the world suddenly shifted to explore the mechanisms behind SARS-CoV-2 action, so, too, did scientific reporting on the virus and the disease it causes, COVID-19. By May of 2020, there an average of 2000-3000 papers were published via peer review and/or added to the preprint server, bioRXiv — a pace that continues even today!

Number of COVID-19-related reports published per week [Source: NIH’s LitCovid]

The RockEDU team was in a great position to help address this problem. Not only did we have access to teams of scientists, many of whom actually work on COVID-19, we have a platform and communication know-how. As a result, Data for the People (D4P) was born!

Article Referenced Above

Cheng VC, Lau SK, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an agent of emerging and reemerging infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007 Oct;20(4):660-94. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00023-07. PMID: 17934078; PMCID: PMC2176051.