Accessibility 101

What is accessibility and why is it important?

Disability pride flag (11)

In a broad sense, achieving accessibility requires that opportunities, events, and information, do not preclude people from engagement based on ability. If something is accessible, we can expect that both able-bodied and disabled people are able to participate and feel empowered in that role (1). Disabilities can be outwardly observable, such as a limb difference, or invisible, such as chronic fatigue or mental illness.

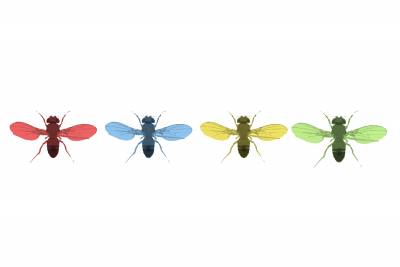

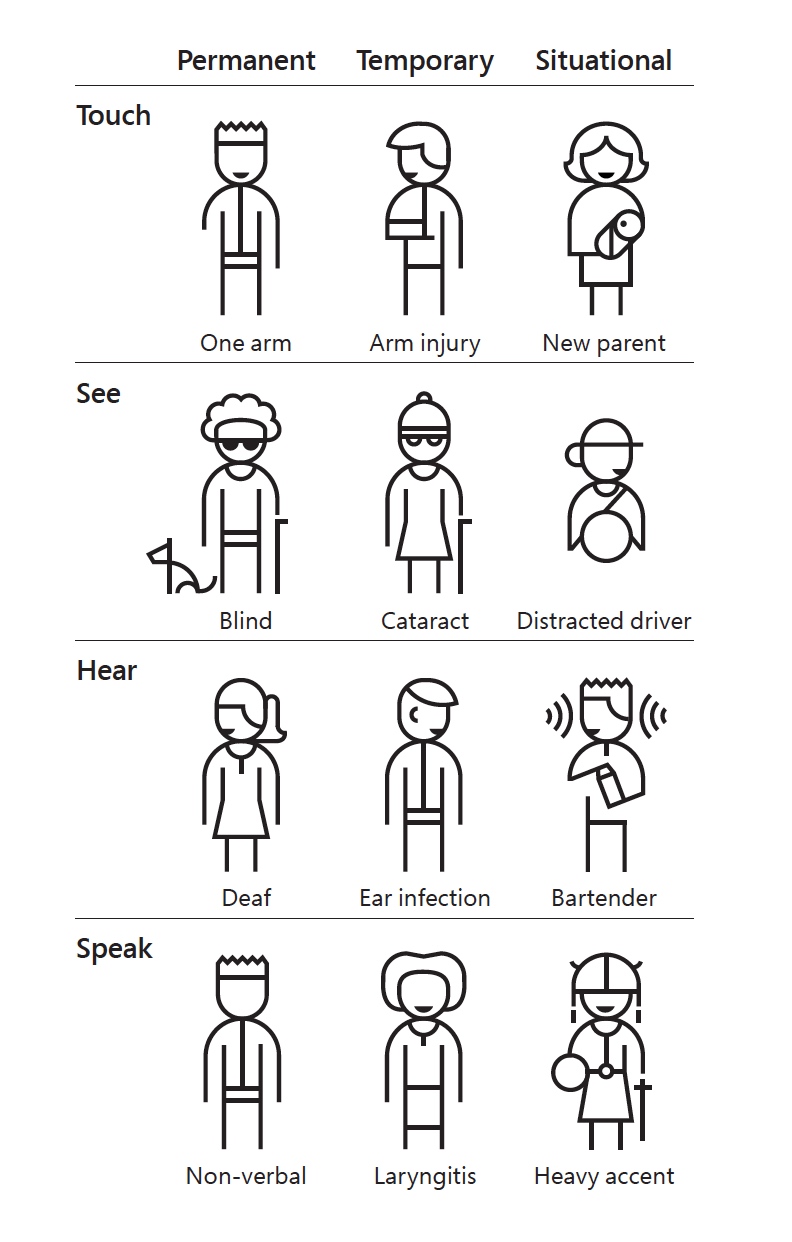

Examples of disabilities cartoon (12).

Access needs are dynamic and vary based on situation and disability. For example, one way to make a conference accessible to a wheelchair user is to ensure clear ramp entrances and swift automatic doors. On the other hand, a conference becomes accessible to dyslexic people when information on slides is conveyed through multiple avenues—including images and auditory descriptions—, not just long strings of text.

The onus of making something accessible should not fall on the disabled person- not only does this force disclosure of a disability, it adds additional barriers to access. As Katie Rose Guest Pryal writes, “Accessibility, [rather than accommodation], means that a space is always, 100% of the time, welcoming to people with disabilities” (4). Accessibility is an ongoing conversation between the able-bodied and disabled communities.

Examples of how to make spaces accessible.

Why do we need accessibility in science?

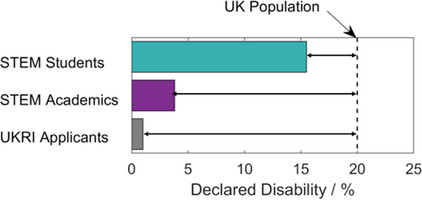

Disabled scientists are underrepresented at every career stage. Few STEM students have a disclosed disability and the number further declines as students assume faculty positions (3, 4). Just as there is a leaky pipeline in retaining non-white graduate students(14), the academy does a poor job retaining disabled scientists. The number of disabled students enrolled in STEM disciplines drops from 10% to 6% between undergraduate and graduate training. In 2018, people with disabilities account for only 2% of the doctorates awarded to US citizens and permanent residents (15). Science should be representative of the community it operates within. By improving accessibility we can remedy systems in education and academia that preclude disabled people from entering and advancing (5).

Disabled people in STEM are underrepresented at all career stages (3).

Diverse scientists bring diverse perspectives and ideas which propel science forward. Take Dr. Wanda Diaz Merced, a blind astronomer pioneering sonification, for example. Her work transforming space-physics data into sound has proven invaluable to deciphering signals from noise (6). Syreeta Nolan, a recent University of California San Diego graduate, uses her experiences as a Black, queer, disabled woman to inform her public health policy and disability advocacy work (7). By following this link you can listen to or read the transcript of an interview with two disabled scientists on the importance of including and elevating scientists from marginalized communities and other topics (8).

Access is love (13).

Additionally, science and medicine directly affect disabled people. When disabled people lead disability research—as scientists or community collaborators—, progress reflects the wants and needs of the disabled community (9). Scientists with disabilities are advancing the fields of ecology and evolution, neuroscience, paleobiology, and many more (10)! In this miniseries we’ll cover some ways in which we can make science more accessible while highlighting disabled scientists and their work.

References

- Alistair Duggin. “Accessibility in government.” Gov.UK. May 2016.

- Pryal, Katie Rose Guest. “Can You Tell the Difference Between Accommodation and Accessibility?” Medium. April 2016.

- J. P. Sarju, Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 10489.

- CRAC. “Qualitative research on barriers to progression of disabled scientists.” Oct. 2020

- Lopes LE, Waldis SJ, Terrell SM, Lindgren KA, ChLInkarkoudian LK (2018) Vibrant symbiosis: Achieving reciprocal science outreach through biological art. PLOS Biology.

- Gibney E. (2020). How one astronomer hears the Universe. Nature, 577(7789), 155.

- Syreeta L. Nolan (2021) The compounded burden of being a black and disabled student during the age of COVID-19, Disability & Society

- Wong, A. (Host). (2019, June 30). Ep 54: Disabled Scientists (No. 54) [Audio podcast episode]. In Disability Visibility. Disability Visibility Project.

- Check Hayden, E. Should you edit your children’s genes? Nature. 2016.

- Caitlin Karniski. “Disability Pride Month at Communications Biology.” Nature Communications Biology. Jul 2021

- .Carlie Rhoads. “Celebrating Disability Pride Month” American Foundation for the Blind. Jul 2021.

- Cole Nussbaumer Knaflic. “accessible data viz is better data viz” story telling with data. Jun 2018.

- “Access Is Love” Disability Visibility Project. Feb 2019.

- Gibbs, K. D., Basson, J., Xierali, I. M., & Broniatowski, D. A. (2016). Decoupling of the minority PhD talent pool and assistant professor hiring in medical school basic science departments in the US. eLife.

- Booksh, K., & Madsen, L. (2018). Academic pipeline for scientists with disabilities. MRS Bulletin.