Styles of Scientific Reasoning

Science is a process for making meaning and deriving understanding about our world and ourselves. It is fundamentally a human endeavor, and thus is fallible in all of the ways humans are fallible. Also like humans, science is a multifaceted, creative, collaborative, and more… Look for examples of science that has been done using each of these approaches, and think about how you make meaning in the world around you!

Consider this…

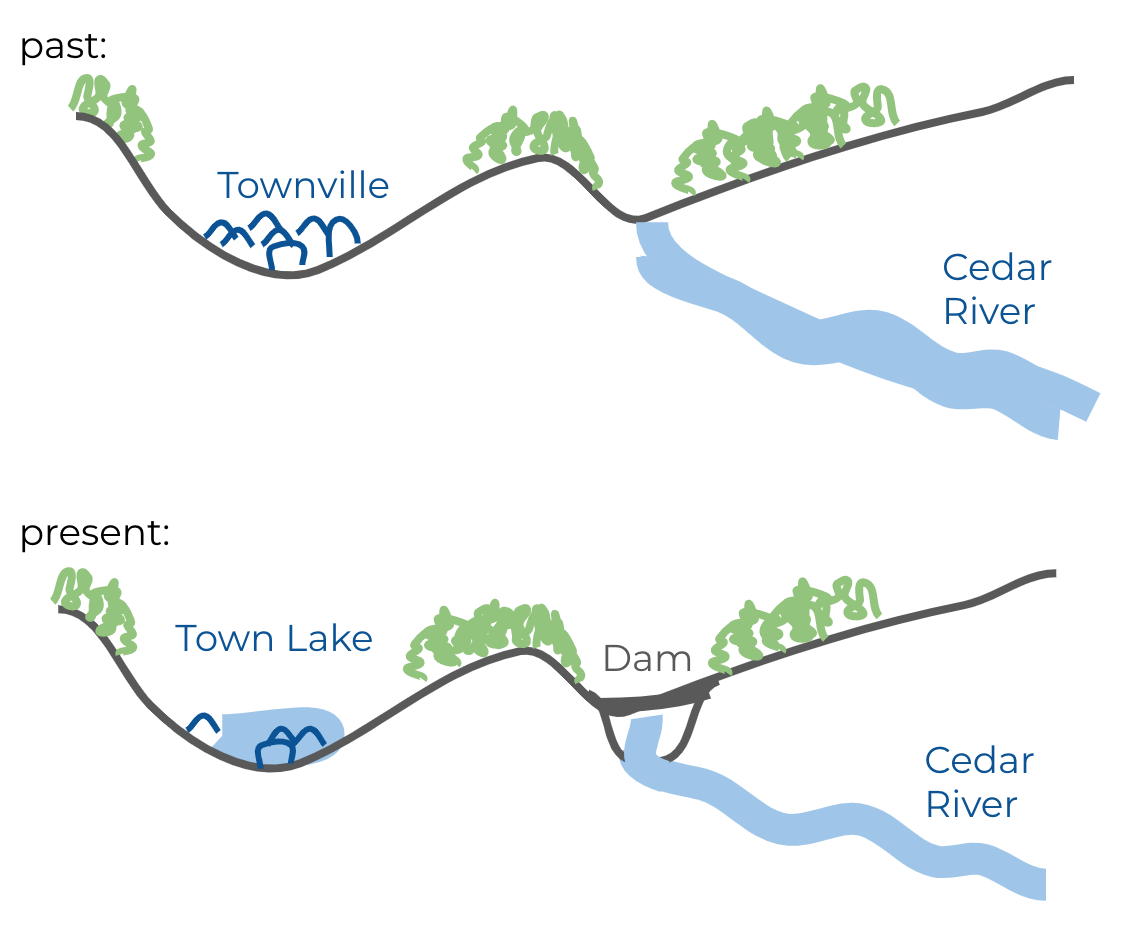

What do you think caused Townville to flood?

To answer this question you are using skills of observation. As this is merely a cartoon, you are limited to what you can see of what is shown. You may want to imagine what additional information you could gather if you were answering this question on site — What other senses could you use? Where would you look more closely? What would you want to know about the bigger picture? etc…

To state what you think caused the flood is a form of stating a hypothesis. While there are many ways of conducting scientific exploration, scientists usually have some expectation of what they’re studying and what they hope to find.

How could you study this?

To move from a conjecture (just a statement you think could be true) into a testable expectation or hypothesis, consider what about this scenario you could examine and support with evidence. What would you expect to find if your expectation/hypothesis is true? AND What would you expect to find if your conjecture/hypothesis is false? This second question is important as it can guide you toward questions that will give you new information about the world regardless of whether you were right or wrong in your thinking. Be humble in your thinking. Leave space to be surprised and to experience awe at what you may uncover about the way the world works.

Try to make a list for yourself of several ways you could study your conjecture/hypothesis. Can you draw on different skills that you have to approach the problem in multiple ways? Imagine for a moment that you have unlimited resources. Also consider what you could do with just the resources and knowledge you have right now. You don’t always need money and fancy equipment to make meaning about the world around you!

Ways of Knowing

If you learned that a controlled experiment or null hypothesis was essential for good science, I’m here to burst your bubble — they’re not. In fact, there are many ways of knowing and deriving understanding in science. We are exploring a framework of six styles of scientific reasoning, based off of the work of Per Kind and Jonathan Osborne (journal link or download here). While sometimes overlapping, these highlight distinct approaches to making meaning about our world and ourselves.

Consider the ways you would study your conjecture/hypothesis for the flooding of Townville.

Did you propose strategies that all fit into one style of scientific reasoning?

Now seeing this list, can you propose additional approaches that use other styles? Consider whether it is helpful to consider the various styles, or whether it’s still hard to think about making meaning in new ways.

Why do you think you stayed within one style? This could be because you’ve identified a lens through which you like to study the world, or it could be a lack of experience with other styles of reasoning? This awareness about yourself can help you in your scientific studies going forward. Find mentors who can help you deepen your skills in a particular style of interest as well as finding mentors who can broaden your thinking into new styles and approaches.

Did you propose strategies that span a wide range of styles of scientific reasoning?

Great—you’re demonstrating breadth and creativity in your thinking. Now, how would you decide which experiment to actually pursue? In this contrived example, you may find yourself drawn to a particular approach that is ethically or realistically feasible (no time travel or flooding of real towns, for example) or to something that requires fewer resources (probably no building of a scale model of the flood plain, though it has been done before!). These are real constraints scientists face and are helpful to recognize and practice—often these constraints help to spur creativity within the realm of the most possible. If you still can’t decide where to start, here are a few more practical tips:

- Start small so that you can fail fast, reflect and learn from your failure, and then iterate to something more meaningful for answering the question. Don’t expect your first idea will be your best idea. It never is!

- Consider what specific question you’d be asking and trying to answer in your work. Make sure the answer you’re looking for will help to answer a question you actually want/need to know the answer to.

- Consider designing experiments/models/etc. that will give you information toward answering your question regardless of whether you achieve your expected result or not. Plan ahead for different possible outcomes, observations, or scenarios and consider how each could add to your current understanding. And know that sometimes you will still be surprised!