Representation Matters

As an undergraduate in the lab, I didn’t want to be defined by anything except for my science. I dressed ambiguously, never discussed my social life or sexuality, and didn’t make a fuss if someone made a sexist or homophobic comment around me. I recognized subtle discrimination, but didn’t see it as an impediment or something that could be changed. To succeed, I simply needed to portray my identity as a scientist, and little else.

There was no glaring discrimination or disrespect directed at me or my female colleagues, though we were occasionally excluded from conversations and dinner outings. Women weren’t a minority in the biology department, but most of us were students while the majority of professors and post docs were men. Consequently, the majority of my role models were male. Still, when I performed enzymatic assays at the bench or did cell culture, there was no difference between my hands and those of the man next to me. “Science is genderless,” I frequently told myself.

My senior year, I took a course titled “Biochemical Mechanisms of Cellular Processes,” in which we mainly studied landmark discoveries and historical papers. Along the way, I learned quite a bit about the scientists behind these discoveries, and was unfazed that 90% of them were white men. Their images became associated in my mind with the primary literature I was reading. At a certain point, my thinking transitioned from “science is genderless” to “science is historically male, but that won’t necessarily stop me.”

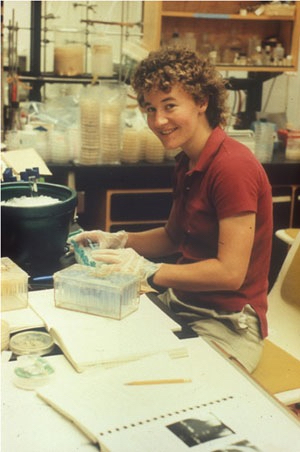

Carol Greider in the laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley in 1985 © Berkeley

Though subtle, this shift likely affected my confidence and belief in my potential.

Near the end of the course, we studied telomerase. I vividly remember a photo of a young Carol Greider at the bench (pictured to the right), alongside a more current photo of her winning the Nobel prize for Physiology or Medicine (pictured, below). With my eyes fixed on the images in front of me, I fleetingly fantasized about having a wildly successful thesis project and contributing to Nobel-prize worthy work, as Carol Greider had done. Though that brief fantasy felt whimsical and unrealistic, it was the first time that I had even considered it imaginable. It was then that I realized how important representation was to me, and likely to my peers. I hadn’t noticed it missing before, but now am acutely aware of its influence.

Carol Greider at the her Nobel Prize ceremony. ©The Nobel Foundation 2009. Photo by Frida Westholm

As a white woman, I do not need to look far for successful and powerful scientists who look like me. I feel represented in most spaces I strive to reach, even if the distribution of men and women is uneven. But as younger generations of scientists become more diverse, so many of my peers do not have adequate representation or role models and mentors who look like them. We not only need to embrace diversity, we need to celebrate it, and make it visible within and between communities. Representation may be our most powerful tool in promoting confidence and equal opportunity for women and minorities in the sciences.