Microbiome: Unraveling Truth From Hype

Editor’s Note: This a rereleased post from a 2016 series that aimed to introduce young, aspiring scientists to topic that sparked their curiosity. In this post, former SSRP student Ella Epstein discussed the science surrounding microbiome research and the importance of remaining discerning when utilizing this knowledge.

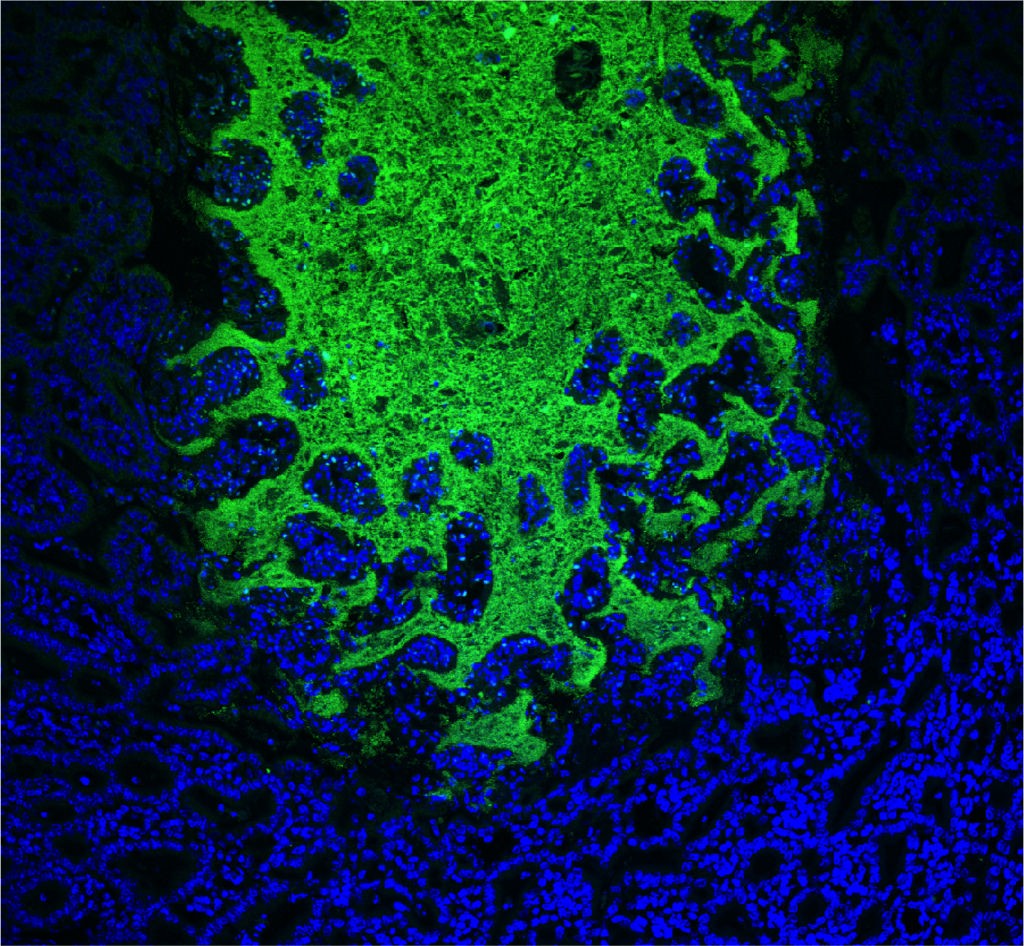

Almost every day, new research emerges on how the microbiome will help us address obesity, protect us from disease, or shape our behavior. Recent research ties the microbial communities inside us to everything from digestive disorders to autism. Scientists are looking to harness and manipulate the microbiome to treat diabetes, malnutrition, obesity, asthma, colon cancer, and more.

If that sounds like an ambitious goal; it is! Scientists have not yet developed any FDA-approved drugs that alter the microbiome. Last month, The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy announced their National Microbiome Initiative, investing over $121 million to “to foster the integrated study of microbiomes across different ecosystems.” As with any sweeping initiative (see the 2013 BRAIN Initiative designed to advance technologies for neuroscience research), hype and truth can often become dangerously intertwined, breeding misconceptions about science that can do serious damage to people’s health.

Some people, feeling like they’ve exhausted the possibilities of modern science, try to hack their microbiome to improve their health. In fact, as we learn more and more about the ecosystem inside us, the number of ways to “cleanse,” “detox,” and “restore” balance in our bodies grows and grows.

Take the booming, billion dollar probiotics industry. People buy these ready-made blends of bacteria thinking they will ‘normalize’ one’s gut flora and lead to myriad health benefits.

What’s more, everyone has a unique and constantly changing microbiome –you can’t prescribe a “one size fits all” probiotic, nor can you expect the bacteria to actually take root.

Currently, there is only one health issue that has a known, reliable microbiome-related cure: Clostridium difficile, or C. diff. As “Flash Forward” podcast producer/host Rose Eveleth explains on the episode “Micro But Mighty,” C. diff is a bacterial infection that “totally ravages the guts of those infected with it.” Implanting a healthy mix of new bacteria acts like a (potentially life-saving) protective shield, allowing the patient’s microbiota to restabilize.

Similarly, Eveleth explains, “doctors are trying to figure out whether children born by C-section might miss out on some crucial microbes that other children get when they pass through the vaginal canal.” Researchers are currently working on swabbing C-section infants with their mother’s bacteria to try to improve their immune systems.

However, microbiome-altering treatments threaten to expose patients to pathogens. Thus, gut bacteria transplants are recommended only as a last resort for C. diff. patients, and some scientists warn of transporting harmful bacteria along with beneficial bacteria while swabbing babies.

Despite these difficulties, a microbe-powered future grows more and more possible every day. In 2013, Dr. Mason’s laboratory launched MetaSUB (originally called PathoMap), a study that aims to map out the microbiome of the built environment of mass-transit systems, focusing on the subway. When they swabbed the NYC subways, “nearly half of the DNA sequenced (48%) did not match any known organism, underscoring the vast wealth of likely unknown organisms that surround passengers every day”(MetaSUB). These organisms could offer new insights into antimicrobial pathways, a promising approach towards combating the growing threat of antibiotic resistance. In three years, MetaSUB has expanded globally, swabbing subways from Moscow to Paris to São Paulo. Ultimately, this global DNA map could improve city planning, management, and human health.

Fields that were previously distinct are now merging thanks to our increased awareness of the microbiome. For example, as cancer-causing strains of viruses and bacteria are discovered, oncology and microbial research are becoming increasingly interconnected. Some labs are working on using the microbiome in forensic science, using bacteria left by an attacker as a novel identification technique that may replace fingerprinting. Dr. Mason himself believes that as this research evolves, the field of personal medicine will as well, and that both bacterial and human DNA analysis will be vital for a more precise medical profile in the future.

As scientists develop the tools to harness the power of the microbiome for human health, we must be careful not to oversimplify their research or overstate the importance of their findings. Rather, much like the trillions of microbes living inside of us, scientists’ discoveries and society’s excitement must evolve together, as a cohesive ecosystem.