Jason Kandybowicz

In his free time, Jason enjoys outdoor activities (such as: hiking, running and skiing), tinkering with vegan recipes and engaging with music (including: collecting, practicing and even producing!).

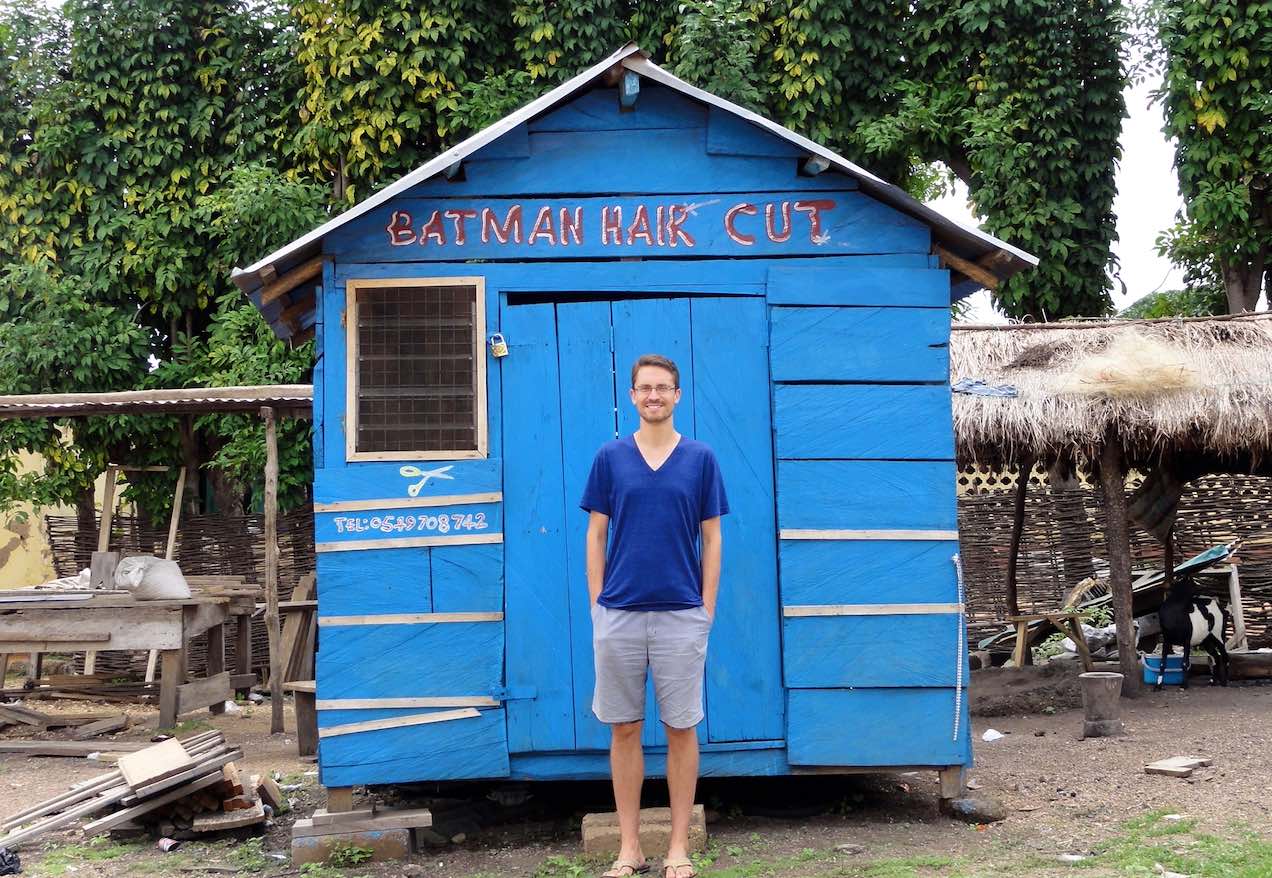

Jason Kandybowicz is an Associate Professor of Linguistics at The Graduate Center at City University of New York (CUNY). Jason researches the grammatical systems of endangered African languages, and when he’s, “not out in remote rural African village or in the classroom, you will probably find [him] in a record shop digging for rare robot music from the UK”!

What’s your favorite thing about being a scientist? Did you always want to be a scientist?

“The most fulfilling life, I believe, is one spent in service of self exploration and the pursuit of inner depth. For me, doing science plays a major role in this endeavor because it is through science that we’re able to transcend our physical limitations and come to know extraordinary things about ourselves and the universe we’re part of. I find this both incredibly humbling and uplifting. When I was very young, before I learned to read, I became consumed by a few self-constructed questions that ended up proving seminal to my intellectual development. I didn’t know it at the time, but my life as a language scientist began with two simple questions before I even set foot in school.

I noticed that the order of pre-nominal modifiers wasn’t fixed. You could say “the big red balloon” or you could reverse the order of “big” and “red” and say “the red big balloon”. I thought about the story of “The Three Little Pigs” and asked my mom why you couldn’t say “The Little Three Pigs”. But I didn’t get an answer. And how could I? My mom wasn’t a syntactician! The other question was for my dad. We were watching a spy movie set in France, where all the French characters spoke English but with a “funny” sounding accent. I thought the language they were speaking was actually French. Since it seemed so similar to English, I asked my dad if all languages were essentially English just with different ways of pronouncing the same words in the same orders. My dad informed me this was not the case, of course, but the idea that all languages were fundamentally uniform at their core fascinated me and gripped my imagination. When I learned about Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar a decade and a half later in college, I immediately thought back to my musings on French spy language and pre-nominal word order manipulation. It was clear not only that I had language in my heart of hearts all along, but that I was drawn to language science because of its potential to reveal deeply important things about human nature . . .”

Why are we alone in the animal kingdom in possessing language? How we develop unconscious knowledge of language? And what properties of language are universal to all human language-users? My favorite thing about being a scientist is that by working toward answers to these great questions, I am fundamentally exploring what it means to be human. And through this exploration, I am gradually coming to better know and understand who I am and what my place in this universe is.

Can you think of a specific time when you found science or pursuing science challenging?

“I research the grammatical systems of endangered African languages. Doing this kind of work involves traveling to exotic remote locations and living in fairly challenging conditions. So, for me, every field research expedition is challenging. Whether its sharing a shower with scorpions, waking up inches away from softball sized spiders or performing emergency self-surgery, fieldwork is always challenging, but endlessly rewarding on both intellectual and emotional levels. The various African communities I have lived among have taught me more about societal inter-connectedness and non-material wealth than I could have ever learned from living in the United States. I feel endlessly fortunate to have learned as much about language as I have about the human condition from these experiences. So, for me, the challenges of fieldwork are completely offset by their tremendous rewards, both academic and personal.”

If you could give one piece of advice to young scientists or students, what would it be?

“Creativity is more important than genius. Curiosity trumps omniscience. Under-explored roads often lead to the most remarkable places.”

Have you ever made something explode or otherwise wildly go wrong in lab?

“Does blowing minds count as “making something explode”? A few years ago I was working with a community of speakers investigating the distribution of question words like ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’, etc. While they weren’t formally trained linguists, a number of these speakers had a sophisticated meta-linguistic awareness that made them functionally equivalent to language scientists. By this, I mean they were capable of making sweeping generalizations about structures in the language and abstracting over a number of facts to arrive at sophisticated and complex hypotheses. After many sessions of me probing the availability of question words in a number of structures and contexts, a number of these speakers independently reached a conclusion about the distribution of these words.

According to them, the generalization was that question words in the language may NEVER appear in embedded (subordinate) clauses. Over the course of the time spent doing fieldwork with these speakers, I had developed a theory to account for this restricted distribution. And like any good scientific theory, my account made a prediction. The prediction was that a certain special rare construction in the language should support question words in embedded clause constructions. As it turns out, the theory proved correct and the demonstration that question words CAN in fact appear in some (but not most) embedded environments absolutely shocked and awed those native speaker consultants who formulated the generalization above. To say that their minds were blown would be an understatement! Mouths agape, they looked at me like I was (in their words) “some kind of language wizard” with supernatural powers. They were stunned by the fact that an outsider who doesn’t speak the language could know something so intimate and complex about the language.

According to them, the generalization was that question words in the language may NEVER appear in embedded (subordinate) clauses. Over the course of the time spent doing fieldwork with these speakers, I had developed a theory to account for this restricted distribution. And like any good scientific theory, my account made a prediction. The prediction was that a certain special rare construction in the language should support question words in embedded clause constructions. As it turns out, the theory proved correct and the demonstration that question words CAN in fact appear in some (but not most) embedded environments absolutely shocked and awed those native speaker consultants who formulated the generalization above. To say that their minds were blown would be an understatement! Mouths agape, they looked at me like I was (in their words) “some kind of language wizard” with supernatural powers. They were stunned by the fact that an outsider who doesn’t speak the language could know something so intimate and complex about the language.

Blowing minds (others’ and my own) is another reason I love science so much.

If you hadn’t pursued science, what would you have done instead?

“I would help recording artists with the ordering/track sequencing of their albums. I grew up in the era of mix tapes and to this day still make them. I put an absurd amount of thought and effort into the order of the songs and the flow/feeling that the ordering gives rise to. For me, 90% of all albums do not have thoughtful or effective track orders. So for 90% of the albums I listen to, I spend just as much time reordering the tracks as I do listening to them. Having done this for several decades now, I would say that I’ve gotten pretty good at it. The real question, though, is would anyone hire me to sequence their album?”

If you were a lab animal/model organism, which would you be and why?

“As a vegan, I’m conflicted about the use of animals/model organisms in the lab. So, let’s change the question to “If you were an animal, which would you be and why?”. My answer to that question is a doe. When I go on long runs, I imagine myself as a female deer, gracefully and energetically bounding through the forest, powered by leaves & plants and characterized by gentility and sensitivity . . .”

If the building was burning, what single item would you grab as you ran out the door and why?

“Since I don’t consider myself or my loved ones “items”, I would grab nothing. No single thing I own defines me or is irreplaceable. (Not even my field notebooks, guitars or record collection.) For me, life is about experiences, not things; inner growth and development, not material reliance or accumulation.”